A long time ago, I posted Part I of this series, which chronicled the unusual history and charm of the Sears, Roebuck & Co. Kit Houses. In this post, I’ve compiled some photos from our house and from historical ads as a comparison. Sorry about the ridiculous delay. Life happened and I haven’t had the time to update here, but I still wanted to put the info out there in case it helped anyone.

Our house is a Sears Van Dorn, which was available only in the 1926, 1928, and 1933 catalog (and actually isn’t fully documented on the Sears Archives for some reason). It’s quite similar to the Van Jean and the Puritan— both Dutch Colonial Revival styles. Rosemary Thornton talks a bit about the Van Dorn here. And that’s pretty much all the info/original photos I’ve found. Anyone else out there living in a Van Dorn?

Here are some of the original features we’ve found in ours (as compared to the Arts & Crafts Society’s checklist):

Stamped lumber- this is basically the only definitive way to tell you have a Sears kit home. Technically some kit homes may not have stamped lumber, either because the buyer chose to locally source materials or because the materials and blueprints were purchased before they were all stamped. Some might have handwritten numbers and some might have nothing. But a huge majority of them do, so it’s a pretty quick and easy way to confirm a suspicion. Each original piece of lumber in the house should be stamped, but the easiest way to check is in the basement (assuming it’s still unfinished). Ours are along the center beam, not around the edges of the basement, so finding them was a little tricky (we also have blown-in insulation so I feared they had been covered up) but I found a note in The Houses that Sears Built that suggested they could face the center of the house instead of the outer walls, and Rosemary was correct!

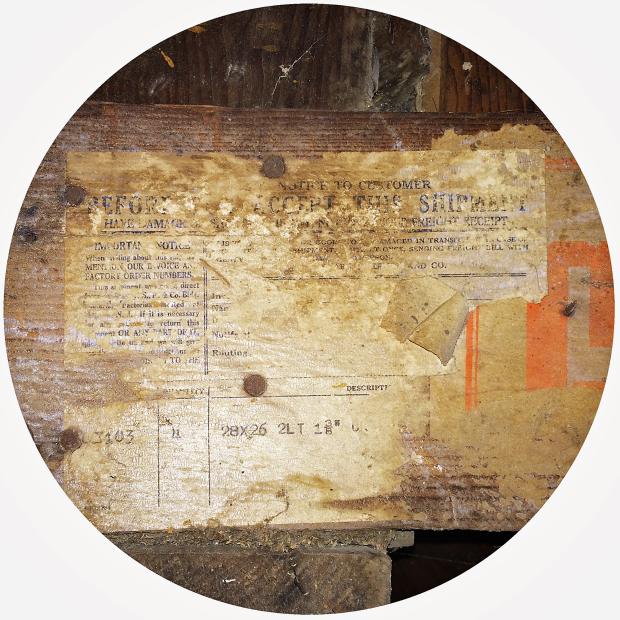

Shipping label– As I was searching our basement with a flashlight for the stamped lumber, I noticed something kind of strange. The back/underside of our basement stairs are held together by wood that is clearly different from the rest of the house. I always thought it was just scrap wood from some old crate, but as my flashlight passed, I noticed text on the wood. I had remembered seeing some of these shipping labels on various sites, and even though ours is too far gone to actually read most of the words, I can just barely make out “S. R. & Co” and some of the other text and stylistic features that are clearly the same as other examples.

Catalog number– As you can see above, the catalog number for the Van Dorn is C1234. I have a note that it’s written in grease pencil in the basement but can’t seem to find my photo of it. Will update if I do

Blocks of shoe molding– these interesting transitions were designed for unskilled carpenters so that every awkward corner and joint wouldn’t have to be perfect. Instead of many angular cuts, irregular joins all have this detail, which is common throughout Sears homes. Our stairway between the first and second floors uses these blocks, but the basement stairs have a much simpler molding that wouldn’t have required as unusual cuts.

Doors and doorknobs– we have confirmed that one of the Sears hardware options for a house of this year (1928) would have been the Narcissus (below), which is consistent to both interior and exterior doors of the house. Our back patio doors are not original, so if I see another set of these at a salvage yard (fingers and toes crossed it will be a french door set!) I will swap them out and make them all match.

Some hinges and latches– I outlined in this post some of the trials of getting the original bathroom hardware back into shape (and here, some of the dining room). The notable thing about the bathroom fixtures was that, under all the paint and rust, the latches were nickel plated brass, which is noted on the original catalog page (above). We also have all the original ball tipped door hinges, although that isn’t really a defining characteristic of a Sears house– they were very common.

Attic windows– we actually haven’t been up here since we bought the house, but are planning on turning it into living space this spring/summer. One thing I did notice immediately was the original semi-circle mirrors on both sides, which is consistent with the original images in the catalog. We have one basement window and one stairway window that are original as well, but they are less distinctive. These windows don’t prove it is a Sears house, but comparing our house to the catalog sketch, they are a quick reference that helps us match it up.

We have a few other original touches, like the medicine cabinet, hardwood floors, and stairs, but they would be hard to identify vs. a non-kit home from the same era. An interesting note is that our floors do follow the same pattern as the catalog says they should– oak in the living and dining rooms and the entryway, maple in the kitchen and bathroom, and yellow pine everywhere else. When we first moved in I thought it was fascinating that every room, even the bathroom, had hardwoods– but they weren’t all the same. I assumed that they had been changed at some point in the home’s history. But looking back it seems that they are all totally original (except in our 1/2 bath downstairs which was made by combining a coat closet and space for an ice box in the kitchen– the floors in there are clearly different which makes sense since it was a combination of two different rooms)

Do you have a Sears house? Is anything fun still left in original condition? I’d love to see photos!

Cheers,

❤ v

As a disclaimer, just because I truly care about the history of this house and want to see how it was originally built, in all its glory, does not make me a professional nor a preservationist. I want to maintain charm in my house but don’t necessarily feel like I need to stick 100% to period for things like furnishings and paint colors. This blog is primarily about our tales of renovating/decorating, and sometimes I don’t choose to go with what’s traditional. I will never take something original OUT of the house, but when it comes to bringing IN new things, sometimes I want to put my own stamp on it since, after all, it is my house. Just in case you stumbled here by Google search and are looking to see a full to-period restoration of a 1928 house, I’m sorry but I can’t promise that. I do mostly shop vintage but sometimes will choose a mid-century or victorian piece to mix in with the deco and dutch colonial stylings of the rest of the house.